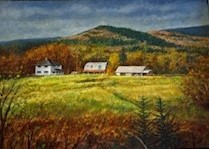

AGORA FARMS – BC

AGORA FARMS – AD

The angelic little community of Corvallis, where Oregan State University is located, was angelic for the white winged only. Hints of this came early, and most conspicuous was that this place had no black people. If you saw one, it was generally assumed to be AOK for two reasons: One, being that he might help the football or basketball teams have a winning season; or two, they had spawned someone to help the football or basketball teams to have winning seasons.

Like most white people, it was convenient for me to ignore such things. Corvallis was adorable, with its volunteer band playing in the park gazebo, in a downtown ripped right out of a Norman Rockwell painting, all with AOK white people.

Then at 3 am one night in 1998, I woke up once and then woke up again.

We had made a special effort to recruit minority students in our National Internship Program. We pushed hard at colleges with large minority student bodies and often provided a little incentive to come out to our lily white, WASP-y little town by paying their travel expenses.

Brandon and Saudia were two of our first black national interns and just finishing their internship at Vote Smart. Both had been at the top of their class and on their way to successful careers, Brandon in the Illinois governor’s office and Saudia working on civil rights in her native Alabama.

They had an early 6:30 morning flight leaving from Portland, so Adelaide and I picked them up in the wee hours for the two-hour ride to the airport. Now this gets a little tricky to explain, it is a “you had to be there” kind of thing. But here is my best effort. I was driving and Adelaide was sitting in the seat directly behind me, while Brandon was sitting shotgun and Saudia directly behind him. In the dark of night, we came up to a stop sign before turning left on to a main but poorly lit street that would head us out of town. Off in the distance, I noticed a police car parked under a tree with its lights off. I turned left, drove five or six blocks when I noticed the patrol car approaching us from the rear. Suddenly he hit his flashers and siren, at the very same instant another police car came screeching around the corner in front of us hitting its siren. Drop jawed, I pulled over.

Completely fuddled, I asked Brandon what I had done, I knew I hadn’t been speeding. He shrugged his shoulders and Adelaide said, “Maybe one of our brake lights is out.” Two police cars for that? I did not think so and watched as the policeman that pulled up behind us started to get out of his car and then put his hand on his gun, while the other car blocked the road in front. Wow! What is this? I wondered. The policeman carefully approached me on the driver’s side, then seeing me, he slowed up and let his hand drop to his side. Now it was he that looked fuddled. Nervously I asked him what I had done. In an odd and equally nervous voice that was pretentiously stern he said, “Never mind, you can go,” and briskly walked back to his car. Both he and the other policeman drove away.

We all sat silent for a moment, then I glanced over at Brandon and then back at Saudia, neither would look at me. I just exploded, I hadn’t gotten it. When we had turned left onto the main street the police car down the block only saw Brandon and Saudia in the windows with two others in the dark shadows next to them. They saw a car full of black people.

My angry rant about getting his badge and going to acquaintances in the press and city council went on for some minutes. When I came up for a breath Brandon and Saudia simply stared at me, and in tag team fashion asked me not to do that.

I was now the student. They told me that if I did those things, it would only make it worse for others. Their suggestion was simply this: “If you really want to do some good, if you want to be helpful, Richard, sponsor some community discussions on racism and tolerance. It will bring it out into the open and help such incidents become less likely.”

The effect those two had on me were in level parts of shame and awe. Of course, they would know what to do, how to respond. Yes, some community discussions, it was the thing to do, the smart, effective, helpful, proper thing to do. But I was none of those things. I was just seething with righteous indignation and by noon I could be found in the mayor’s office, unrolling an obscenity-laced review of the night’s events.

She, of course, promised to have a stern talk with her Chief of Police who would make sure his patrolmen were properly chewed out, certain to magically result in a more respectful attitude toward people of color.

I had stirred up a nice angry pot and could now, like most of the self-righteous, point my countenance skyward and arrogantly walk on, having done exactly what Brandon and Saudia asked me not to do – busted some ass to create peace on earth.

We had great groups of National Interns. We were quickly becoming dependent upon their full-time efforts in 10-week shifts. We made great progress and had a lot of fun events out at our new Agora Farms. The students started something of a ritual where each student got to pick a tree and plant it. We had peach, apple, cherry, walnut, hazelnut, even some sequoias.

The students, my God the students! There were more signing up to do national internships than we were able to accept-young passionate and chomping down the work in enormous gulps. They came from everywhere and in the end 14 different countries would be represented. The G-7 asked us to make a presentation. The State Department, having money to burn, asked us to send representatives to some newborn democracies in Africa and Eastern Europe to show how we did what we did. They were fools’ errands to be sure, not a one could yet cough up any open records to do what we do. Poor Lorena, who had been with me through every tangled twist, volunteered for the trip to Mongolia where she slept in yurts and choked down roasted yak while fending off some Mongolian chieftain in heat.

Some interns were just over the top extraordinary, like Tsering. Tsering was a student from Tibet who hiked seven days over the Himalayas to say good-by to his Tibetan parents before flying to America for college and coming to Vote Smart. And there was Mia from Beijing, who became Tsering’s best friend. The two added a “Chinabetian Tree of Peace” to the growing saplings at Agora Farm’s.

I was giddy with fresh hope. Then one of the students who had just arrived, Saudia, (the same bright young black women I would drive to the airport ten weeks later), asked if I would teach her how to fly fish on Mary’s River, that little flush of water that ran through our Agora Farms.

I grabbed a couple of rods and Saudia and I walked down into the little river. She took to the casting of a fly rod like she was born to it. She didn’t manage to catch anything and I only one tiny seven-incher, but we had a great time, and she was hooked on the sport. Putting the rods away, I promised her that she could use them anytime she wanted to give it another try, and she headed back to campus.

Barely a toilet visit later, a slightly grungy, short, light haired woman came stomping over our bridge and up the driveway. Her manner, walk and expression were all contorted as if struggling to control pressure in her steam kettle by attempting to shove a cork in its spout. I was about to catch hell and knew it, but about what?

“We do not want any of these people in our water!” I recognized the woman behind the grotesque anger of her expression. She was a professor the university promoted as a kind of nature lover, who, I think had actually written about the stream Saudia and I had just been fishing in.

I really didn’t grasp what she had said and responded with something like, “Sorry, there must be some misunderstanding, what do you mean?” She softened her expression and more calmly said, “We don’t want any of these people coming and getting into our river.” Still confused, I asked whose people. Returning to her more aggressive attitude she blurted, “I know you were in the water, walking down our river with (hesitation) some newcomer. This is our river and we do not want these strangers in it.”

I cannot remember what I said next, but it wasn’t angry. I was simply thinking I could not have heard her right. But within a week it was clear. Inhabitants on the other side of the little forested river, and many beyond, suddenly became aware of an amazing array of nonsense. Before they were done, I would hear every sort of story bedecked in the horrid things we had secretly planned for them all. A few were not too delicately pirouetting around their fear: “NO NIGGERS HERE!”

When the more serious attacks began, those who opposed the construction of our research library (a size little more than your local coffee shop), had persuaded a fellow academic, to testify to the dangers of having a building of any size built on such unstable soil. When I pointed out that the soil on that same hillside, not a stone’s throw away, had safely supported an Iron Horse whose rumbling daily deliveries of lumber equal to a thousand libraries for the better part of a century, it did not dissuade or embarrass. But the zoning board quickly and unanimously supported our plans for construction.

The storm raged on, in the end good sense, reason and fairness lost and democracy won. In democracies, when the mob gets going that can happen.

The naturalist’s rabble, eager to keep students of a certain sort out of their river turned up the heat on us with middle of the night threatening calls and our mailbox full of manure. They did much the same to the County Commissioners, who were forced to reverse the decision and deny us the permit to make Agora Farms a reality.

We had raised $400,000 from members to build that research library. Humiliated by my failure in what I thought a sure thing, I wrote each of them an apology, saying I would refund their contribution.

What happened next would steel my resolve for two decades more. If my effort to build was a failure, my effort to return the funds was a tragedy. In the end, I did not have $400,000 but $475,000, with an almost universal reaction, “GET GOING!”

(New chapters will be added roughly once a week)

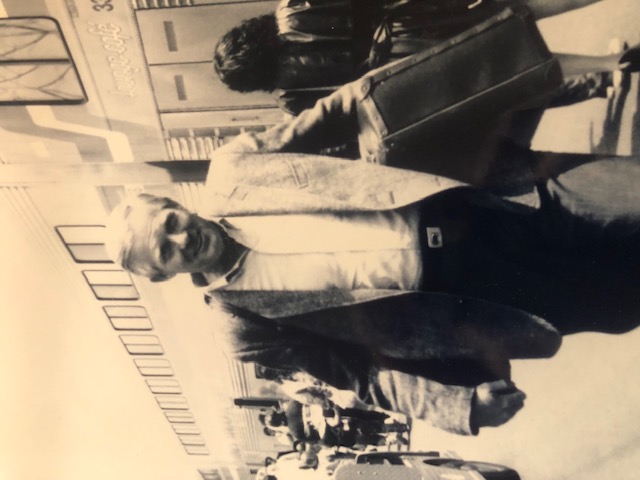

Richard Kimball, Vote Smart Founder 1988

Sign up on my Blog at: richardkimball.org

or

Medium.com at: https://medium.com/@daffieduck2016