CHAPTER 34 – THE MIRACLE OF ME

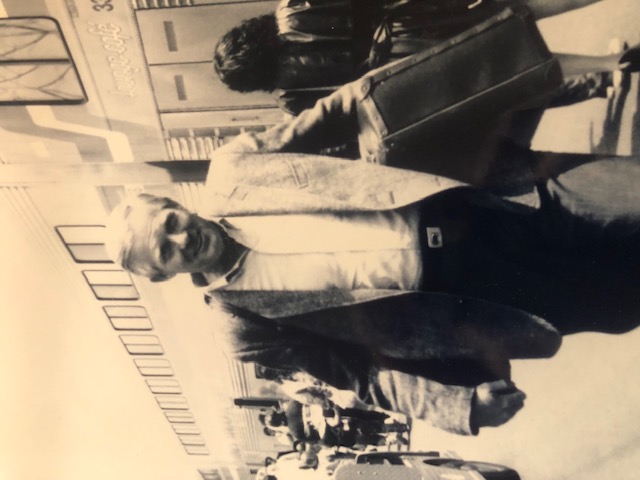

U. S. Senate Campaign

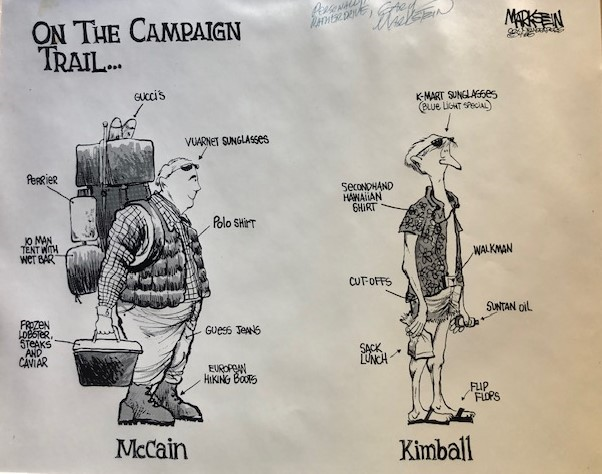

Newspaper Cartoon

U. S. SENATE CAMPAIGN

Good fortune can appear in frightful packages. A fearsome Republican newcomer had moved to Arizona and entered its politics. Married to wealth, a former prisoner of war with the pent-up energy of a caged pit bull and temperament to match, he scared the Hell out of Arizona’s Democratic governor who had been drooling over the Senate seat being vacated by America’s conservative lion, Barry Goldwater.

Not unlike me, McCain had been a poor student, at the bottom of his class, focused on anything but school, he was unconventional and would invest every ounce of his energy when running for office or fighting for what he believed was right.

Unlike me, he had money, lots of money. And he had survived five years of misery in a Vietnamese prison camp while I was enjoying the good life, safely barking about bringing him and every other soldier home from a fool’s war that went nowhere and advanced humanity nowhere—a farce that served only to feed the supersized heads of idiots that insisted upon it. Yes, I barked and barked and then enjoyed another kegger with my frat brothers—all while McCain was kicking back on his prison cell floor after being busted up again.

As one operative told me shortly after McCain won a seat in the House of Representatives, “One day you are going to run into that guy.”

It would be a changing of the guard. Goldwater, who had almost single-handedly bent the nation towards a more cautious, conservative road, had become exasperated by the religious and political fanaticism that had twisted his road into intolerance. Over the past dozen years or so, I had grown to respect and admire this retiring political icon. This, in spite of the fact that years earlier when I was 15, Stevie Bogard and I walked into a Goldwater for President headquarters and pretend to be volunteers. We told his office that we loved Goldwater and wanted to do what we could. We took all the bumper stickers that said Goldwater, left and then went out and pasted them under stop signs around town. We, of course, were certain that drivers would read it as STOP Goldwater, a perfect representation of my level of political sophistication at the time.

Anyway, Goldwater had announced his retirement, thus opening a seat in the “world’s most powerful deliberative body.” McCain announced his candidacy for the seat and over the following few days our governor and other well heeled, well known, Democratic big names fought over just the right words to explain their deep sorrow at not being able to run at this time. As they galloped away into a sea of “prior commitments,” one of my influential supporters crudely put it, “What do we know about this guy other than he can’t fly and he can’t escape.” And with that, I realized my opportunity to cop-out on the last three years of my Commission term.

I knew I would have little chance, as one cartoonist later graphically displayed, with a roulette wheel showing me as the double digit zero and McCain with the rest.

So, I announced, and the horse race polling instantly began, showing me with 16%, or put another way, roughly the same number of people that still think the world is flat.

To me 16% was a surprisingly large number and given the choice of a few more years on the Commission or the chances God gives snowflakes in the desert of becoming a U. S. Senator – I became a flake.

It would have been such a simple matter to stop me. Any other Democratic candidate willing to make a fight of it would have instantly backed me off and sentenced me to those three more years of Corporation Commission Hell. But no one else came to the stage, no other so imprudent. As a result, I became the Democratic nominee to challenge the unbeatable, well heeled, heroic, teeth gnashing John McCain.

My biggest problem, as I was quick to discover, was that I wanted it. I loved Arizona, its rich history, the people I had grown up with, the smell and taste of the state that only a child raised in its flavors could truly feel a debt to.

Unlike almost every other elected official I had ever met, I had never really acquired a taste for the power ingrained in elected office. I just didn’t much trust others to have it. The only time I enjoyed my soon-to-end political career was when I was campaigning. I had just loved meeting people, occasionally being recognized by strangers, and talking about stuff. People in their homes or just out on the streets were never on the make. No manipulation, no ego (minus mine of course), just their thoughts, passions, worries and ideas. Granted, some ideas could be a little off the wall or lacking the practical reality that comes from swimming in pools of the politically ambitious.

The notions of citizens were usually honestly arrived at, thoughts and ideas were equitably intended, if not well informed, while those in the halls of power were well educated but almost to a person, self-promotional.

Spending real time with real people wasn’t done in campaigns for “Big Ticket” offices. To be taken seriously, or at least not embarrass myself, I would have to raise $1 million. To have even a chance of winning, I would need four times that. That was back in the 1980s, when U.S. Senate seats were very expensive by historic standards and dirt cheap by current ones.

Despite that fact, my campaign naively started like all my prior efforts had, going door to door with friends and family. I was going to do this right.

One of the things that going door to door gives you is a lot of time to think, particularly when no one is home as it was on my first day knocking. As I walked, I daydreamed this calculation: Imagine, I thought, that at the next house there was not only someone home but that they were having a party with two dozen guests. They invited me in and gave me an hour to tell them why I was doing this crazy thing and listening to what they had to say. Then I imagined that there were a few dozen at the next house and again at the next, and every house ever-after. I did just that and never took a day off for all the months left to campaign. Not only that, but I was so brilliant, so articulate, that every single one of those people fell in love with me and voted for me on Election Day. It added up to a little over 2 percent of the expected turn-out. That is not how you get to be a United States Senator.

Anyway, when I did give speeches they were about things I wanted to say, they were heart-felt and passionate, and after a few weeks I started to climb a bit in the polls.

After a month or so I thought we were doing OK, people were holding bake sales, stuffing envelopes, and having little receptions. Even my brother Bob, a teacher who had just enough money to buy his clothes at Goodwill, somehow put together the maximum and gave me $1,000. We had raised $25,000 in our first month, a lot of money–or at least what I thought was a lot of money.

I had climbed from 16% to 25% in the polls.

It was then that I got The Call. The kind of call that all potentially winning, or perhaps just useful candidates get in one form or another. Mine was from the AFL-CIO. It seems they knew I was often partial to people who worked but it was unclear why they thought that should translate into their support, since I thought union leaders could be no less corruptible than their white-collar counterparts.

Moreover, most union members seemed oblivious to what was happening to their jobs. The country’s corporate leaders were deep into replacing them with cheaper slave labor from abroad, where workers struggling to get a cup of rice or a tortilla into their child’s stomach were much kinder to their bottom line. Corporations reducing costs flow toward cheap labor where workers are un-hobbled by freedom, fairness, equity, or any other advance since the invention of the whip.

Anyway, when The Call came, I acted just like the puppy dog they wanted, and I was. Knowing McCain would spend millions I was anxious and immediately hopped on the plane to Washington.

I was taken to the AFL-CIO building, constructed during organized labor’s hey-day on the opposite side of Lafayette Park from the White House, with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce just across the street. When I walked into the front door, I was met by a few labor leaders and led upstairs to a tiny little room where a few members of the United States Senate sat, along with a couple of other wannabees just like me. It was an odd feeling sitting there–waiting for what, I was not sure. But then the door opened and one of the Senators got up and went into the next room. Ten minutes later another was called in, then another and another, until finally they called me.

I walked through the door and entered this enormous conference room. The conference table in the middle seemed to stretch for a city block, with large carved mahogany medallions of historic labor leaders hanging high on the walls. Labor heads from across the nation sat in large leather chairs, some lazily pitched back smoking cigars as if out of a Frank Capra movie. I knew no one in the room; the Senate hopefuls that had preceded me had been excused. For a newcomer to the big game, it was intimidating.

I was introduced and given a few minutes to tell them about my campaign and how I might win. My talk started off a bit clumsily as I recall, and I assume that I talked with some passion about people that worked, but the truth is I really do not remember what I said. When I was finished a Mr. Perkins, their Chair, said, “Well, Richard, we think you might be able to pull this off and we would like to start you off today with this $50,000 check.” He had the check in his hand.

Boy, I thought, whatever I said was really effective. I was so effective that they were willing to break the law and start me off with an illegal campaign contribution exceeding the legal limit.

I objected and pointed this out. Mr. Perkins smiled and put his arm around my shoulders much the way my own father used to and said something that would be repeated by others during the months that followed, “Now, Richard.” Then he went on to explain, “No, no, you don’t need to worry about that. It’s all legal. See, we all represent different unions, with our own memberships, our own Political Action Committees. We simply like to bundle our funds and spend them collectively for greater impact. It’s all legal,” he assured me.

I thought about it a moment and then, like any prudent politician, I stuck my hand out for the check. What happened next, I cannot say I recall with perfect accuracy, but my recollection here is fair or at least the best I can do.

As I stuck out my hand out, they put in it, not the check, but an 8.5 x 11 sheet of paper with maybe a dozen names on it. Then they told me that they wanted me to spend the first $20,000 of the money to hire one of these pollsters they had confidence in.

Mr. Perkins said, “We want to see what people in Arizona like about you and what they don’t, what they like about McCain and what they don’t.” I was not all that interested in doing such a poll but I understood their need for one and said OK, thinking I would make good use of the other $30,000 and again stuck my hand out for the check.

Again, they handed me another list of names. “These are some people with trophies on the wall. We want you to spend another $20,000 as an initial payment to one of these trophied consultants who knows how to design effective campaigns and create successful messages.” The trophy remark was in reference to victories they had produced in other congressional and gubernatorial races in the country.

Now I had my dander up. “This is my campaign,” I barked. “I am running because I have some serious differences with McCain on Star Wars (missile defense), Contra Aid (U.S. sponsored revolution) and other crucial issues. I am going to run my campaign and say what I think,” I told them.

“Now Richard,” Mr. Perkins said again, “We

don’t want to stop you from saying what you believe. But we aren’t stupid, Richard. We aren’t going to just hand over this check and say, ‘Have a nice day, you sure seem like a nice guy, good luck to you, hope to see you in the United States Senate someday.’ “Don’t be stupid, Richard. “We need to make sure you spend this money wisely, have the talented help who can emphasize those things you believe, that the citizens of Arizona believe, because WE NEED YOU, Richard, IN THE UNITED STATES SENATE.”

That last line felt pretty good, my head swelled a bit and besides, to say “no” would admit that I was stupid. My being so out of my element and in such unfamiliar surroundings and company, I wasn’t certain I wasn’t. Stupid, that is. Why provide additional evidence. Their argument seemed logical; they weren’t asking me to lie outright. I could say what I wanted, and they were going to help get the person the country needed into the United States Senate — that would be ME!

So, I took the $50,000 as I would a dozen or so other such checks from special interests and pranced off and into political oblivion.

(New chapters will be added roughly once a week)

Richard Kimball, Vote Smart Founder

Sign up on my Blog at: richardkimball.org

or

Medium.com at: https://medium.com/@daffieduck2016