New Year’s morning I headed back to that ranch and there it was, only now under sparkling, rich, deep blue skies and framed by 10,000 ft. snow covered peaks. As I rolled up to where I had parked the day before, the reverence that trawled over my face would have given me away to anyone. We would buy!

To this day it is one of the most beautiful sights I have ever seen. Everything on the ranch was a wintery incrusted jewel. By the time Adelaide, my soon-to-be wife crept down those last 12 miles of ice slicked dirt and petrified by the thought we would be so remote, I was ready to write the check. The oddities of life would one day make her cherish the place and me dread every moment I had to be there. But for now, it was paradise and exactly what Vote Smart needed.

Fortuitous, we closed the deal on April Fool’s Day, 1999, for a modest $1.25 million, about half from the sale of our Agora Farms in Oregon, and the rest coming from supporters anxious for us to “GET GOING!”

Wanting to consolidate our offices at what I was sure would become the epicenter of all that was good and true in self-governance, we informed both Oregon State University and Northeastern University that we would be closing our operations and consolidating them at our new Montana paradise. The decision to close our Northeastern office, a wholly successful operation that sang as smoothly as a tuning fork, would be a mistake I would later attempt and fail to rectify.

The ranch had been used as a “city slicker” operation where the owner outfitter catered to rich Easterners who wanted to go West, play cowboy, ride, shoot and fish. He went belly-up, because money doesn’t prevent saddle sores or make you superior to a bear having to take a shit in the woods.

The property had a number of advantages, the most obvious being its dazzling setting on the Continental Divide, handing us our new home’s name–The Great Divide Ranch on the road I renamed, One Common Ground.

Three practical factors convinced me that this beautiful place could work. One was that the utility company was willing to put in underground fiber optic cable down those 12 miles of dirt road, providing virtually unlimited communications ability–much better than we ever had sharing university systems. Then we discovered that the public access road to the wilderness went right through the Ranch’s property, and a long-ago prior owner had made a deal with the Forest Service. They could use the property for their road, but they had to keep it plowed free of snow each winter, meaning that we had year-round access. Finally, I met with the County Board of Supervisors about emergency services. They all assured me that it only took 5 minutes for the Life Flight medical choppers to pop over the mountains from Missoula. It was a lie that later would cost two lives!

I, of course, had no idea how to run a restaurant, hotel or recreation facility, yet we were about to double the size of all other such facilities in the county put together.

At first glance Philipsburg, the closest town, was just a down-on-its-luck abandoned mining town, where you could buy a house cheaper than a car, with four abandon churches and just as many bars opened to replace them, serving it up from early morning to its 957 citizens.

Those still living there were largely uneducated, unemployables, I would employ and make it a day or month.

A few progressive citizens were trying to champion the little town as a tourist attraction and would eventually succeed, despite the “We Don’t Serve Queers,” and Confederate Battle Bars flag holding sway over most locals.

I had a six weeks to prepare the place and move our equipment, programs with whatever staff was willing to transfer, if only temporarily, to help train new research teams at The Great Divide Ranch no located on One Common Ground.

I lived at the ranch alone, working with contractors, cleaning and converting the storage building into offices, and hiring new staff. The applicants were mostly local Montanans, with a good number from the little town of Philipsburg, all a little rough, but assuring me that they were intensely interested in good government. There was the liquor store manager, a former radio disc-jockey, a handyman who had recently lost his job working on a friend’s ranch that had to make some layoffs. . . and Aili Langseth.

I scheduled the job interviews all for the late afternoon and at the ranch so they would have to make the drive and see what they were in for. I was prepared to hire almost anyone because I figured if they were willing and committed to the effort, I could train almost anyone.

My first days were spent cleaning out the half century of odds and ends that had accumulated in the storage building. Old wagon wheels, stoves, horse tack and a thousand other indescribable somethings, were stacked from front end to back end almost to the ceiling. I pulled out the most interesting pieces and scattered them around the property thinking they would have novelty value and add to the ambiance for those who would come.

On a final afternoon of cleaning, a day before the electricians who would re-wire the soon-to-be-office building would arrive, I was in a big hurry. I had scheduled my first applicant interview for 5 pm and I was a dirty, shirtless, sweaty mess. I had not started the day half naked. In fact there was snow on the ground when I woke up that morning, but by 10 am it was long gone and getting pretty toasty, so I yanked my sweatshirt off for a time. By 1 p.m. I was racing to put it or anything I could find back over my shoulders. Heavy clouds had rolled in and were punishing me with marble-sized hail which turned into snow 10 minutes later. By 3 p.m. it was clear and once again the sun began to burn. I had never seen such weather. By 5 p.m. the temperature and my struggles dragging out every imaginable bent, broken or otherwise indescribable whatever had me ready for a quick shower and the one interviewee I had scheduled for that evening.

I picked up one last, exceptionally large box full of canvas and broken sticks, what I guessed were bed slats, and began walking it from the office building the 100 yards to the lodge. From behind me I heard what I can’t adequately describe, simply because I had never heard anything that sounded at all similar. I can only say something was coming.

The box was so large I could not balance it to take a look, so I just kept on walking. But the sound got louder and a whole lot closer. Another step or two and panic would set in. If I had to describe the sound with some mash-up of letters it would be something like this: fflooomp…………fflooomp…………FFLOOOMP!!

It was right on top of me and I dove forward into the dirt with the box breaking open and spilling its contents across the cold mud.

I put my arms up to protect and defend myself as I rolled over to see an amazing sight pass not ten feet directly over my head.

Fflooomp! is the sound a Bald Eagle with its gigantic wingspan sounds like coming in for a view of its own. It was my first and most innocent experience with the wilderness wildlife yet to come.

I picked myself up, showered and sat in the lodge making some calls until late evening. The applicant, some young lady named Aili Langseth, never showed up.

At seven the next morning I was on a conference call with people back East when someone startled me with a knock on the lodge door. A young, good-looking though rumpled woman walked in and quietly took a seat at the old copper bar on the far side of the room while I finished my call.

When done and a bit hassled with too much to do, I blurted out, “What can I do for you?” She responded, “We had an appointment about a job, I am Ailee Langseth.” Irritated, I explained to her that my only appointment that day was with an electrician. She said, “I know, our appointment was for yesterday afternoon, but I couldn’t make it.” Suddenly I remembered and my irritation increased, and I said, “Well you should have called. So what are you doing here now?” Then I heard the rest of the story.

It turns out that she would have been on time for the interview, having left her home in Butte, a town ninety minutes away, in plenty of time to drive the 65 mountain miles to get to the Ranch. But when almost there she had taken a left turn, one dirt road too early and had ended up stuck in the snow on a road to nowhere. She had worked until dark trying to dig herself out but only managed to get herself soaking wet in the freezing slush. So, she crawled into the corner of the back seat, with a blanket over her wet clothes and sat out the night trying not to freeze. Later I would look up the low temperature for that night: it went down to 28 degrees. She joked that that she sat there through the night thinking of the cold hungry people in Bosnia, where, at the time, conflict had left so many people freezing and homeless. “If they can suffer through it, so can I,” she explained.

At first light that morning a fisherman saw her and was able to tug her out. Aili Langseth did not drive home to get warm that morning, nor to get some dry clothes on, or even something to eat. She kept coming on to the interview, to apologize for not being on time the afternoon before.

When my jaw managed to return to its proper facial position, I said, “YOU’RE HIRED!”

(New chapters will be added roughly once a week)

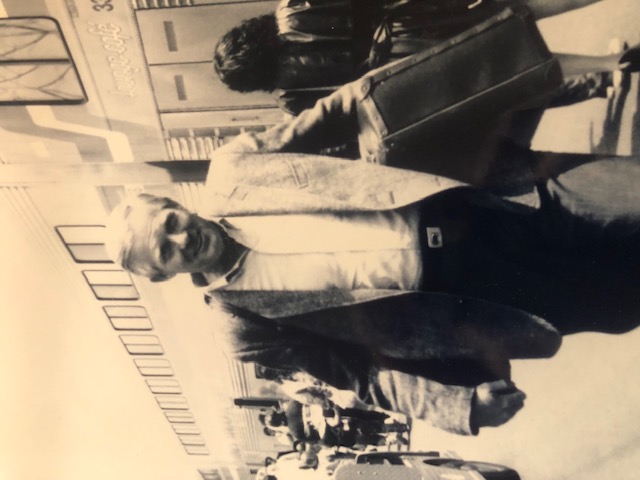

Richard Kimball, Vote Smart Founder 1988

Sign up on my Blog at: richardkimball.org