WALKABOUT: noun A short period of wandering Bush life engaged in by an Australian aborigine as an occasional interruption of regular work.

For months after the Senate campaign, I did nothing. My frenzied life over the years suddenly ended and I was completely unprepared for what was laid out before me. What was before me was an enormous pile of zilch.

If your training is in politics, you’re not trained for any real people work. With no job, no degree, a small home and about $8,000 in retirement I was done.

Some people suggested I could beat the local Republican just elected to our Congressional seat. A good fellow I had served with in the State Senate. It was either that I thought, or strap on a backpack with a few necessities and do my “walkabout” somewhere with a lot of different.

Now before America’s craving for illegal drugs fed, watered, and fertilized blood-thirsty cartels willing to sell them to us, before overdose deaths tripled, and before half of all Americans over 12 years had or were seeking illegal drugs, disappearing in Mexico was pure vagabond enchantment.

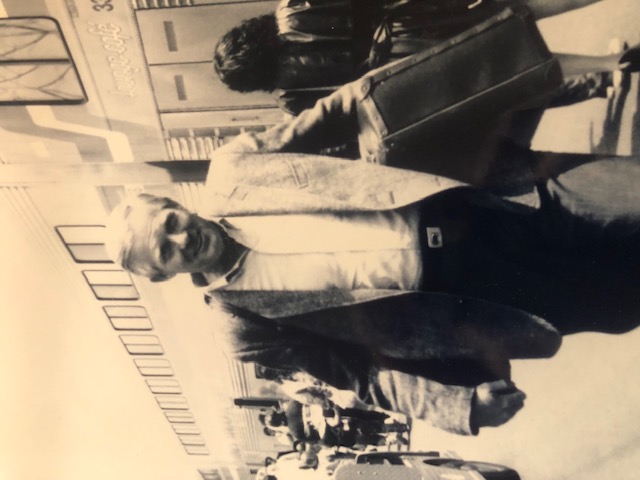

Using legs, buses and trains, I backpacked for months, meeting an amazing assortment of wonderful people with a sprinkling of crooks tossed in. I had a loose itinerary where I would show up in cities and towns from the American to Guatemalan border where I knew that the Mexican presidential candidates (the crooks) would be speaking. I fell in love with the Mexican people, their innocence and heart melting unpretentious charm offered up in town after town, even as the civic culture punished them for that innocence and made me long for the relative integrity of the U. S. variety. Not having taken Spanish at the University, I could understand little of what those I met said.

So, when I stopped in a place called Cuernavaca and met a family willing to give me a room, bed and meals for next to nothing, I went to school for a month of intense Spanish training. I worked at it hard. Every day after classes I would give myself assignments that forced me to use that day’s lesson.

On a Sunday, I saw this enormous mango tree bursting with plump ripe fruit. The tree towered over a little brook in a lush postcard pasture, simply bursting with butterflies. Since my oldest brother and been collecting butterflies almost since birth, I decided my assignment that day would be to go around town talk to people about mariposas and purchase all the necessary things needed to construct a net to catch them. When it was done, I returned to the pasture to see what I could catch. Ten minutes into my chasing and swiping I heard children laughing. I stopped and looked up the hillside to see an elderly woman, young mother and two children giggling at me. It was instantly clear what a sight I must have been. This 6’4” 240 lb. clumsy American stumbling through a pasture swatting at insects. I started to laugh too.

Anyway, we started up a conversation. I could say just enough to communicate the basics of my enterprise, mariposa and coleccion. I understood little of their Gatling Gun fast responses, but it was clear they wanted to see what I had caught, so I showed them the three or four I had managed to capture in a little box. Then the children asked, and somehow I got it, would I like to see their coleccion too? I followed them down a path to their home on the muddy bank of the stream. Dozing in a hammock near an open fire, where what looked like a giant pizza tin was heating up, was the father. He sat up, smiled, while pointing his finger at what was his tree stump-of-a-seat offering. The home was nothing more than a few boards with cardboard panels tacked along the sides. The roof was a combination of old, rusty, twisted up tin sheets and palm fronds.

One of the little girls disappeared into the vegetation while the others kept jabbering so fast I could not pick out the words, but it was clear they were talking about me. The smiles, laughter and friendliness were a joy to watch and be a part of. They clearly did not often have visitors. If it had not been for the shack of a house, dirt floors and pounds of laundry hanging on wires strung through the trees, these folks could have been stars on a Mexican version of The Brady Bunch and I might have accepted their offer to let me stay with them.

Then the one little girl returned, arms filled with a half dozen little glass jars, each one holding a dead, largely decayed snake in some sort of fluid. That was the collection they wanted to show me and I examined each with real wonder. They all continued to spew out words so fast, I had to ask them to speak more slowly in the hopes I could pick out a few. After numerous requests for them to “repetir,” and considerable effort to patch together some meaning, I finally got it. If I had understood every word, the conversation would have gone differently, but I didn’t so it went something like this: They had been asking me where I was staying. I had been responding with the word “no,” meaning I did not understand what they were saying, but they decided I had “no” where to stay. The same miscommunications happened regarding my eating. When all was said and done, I suddenly realized that they were now asking me to dinner, offering their hammock as my bed and saying I could stay with them as long as I needed.

Such were the people I met all through Mexico, wonderful, generous with all they had, which for the hideously disadvantaged by their so-called democracy, was nothing.

The only exceptions to these wonderful people were their “on the take” politicians and one diminutive old lady at an unusually uncrowded train station. On a quiet Sunday I was getting on a subway in Mexico City to go to Maximilian’s Castle, when it seemed that all the few others waiting chose the same door as I to get on the train. It was a tight squeeze and I did what had been my habit and put my hand in the pocket where I knew my wallet to be. Only this time I found another hand in my pocket with my wallet in it. I turned to see who it was and it was a tiny little lady somewhere in her 40s or maybe 70s (ages can be hard to tell in Mexico), who looked up at me with an embarrassed expression and said “Oops.”

“Oops?” I repeated, “Is that Spanish or English?”

One of the Mexican presidential candidates came to the little town I had chosen for my Spanish lessons. A fellow who would become Mexico’s president named Salinas de Gortari. His party, PRI, had planned a celebration and parade down the main street. I went a little early to get a good view. Maybe one or two thousand people were milling about on both sides of the long avenue. I waited some twenty minutes past the appointed hour. Then a hint that the parade was in progress—a small group of four or five musicians that walked by dabbing at their musical instruments. Following them there was just a bunch of stragglers, mostly in suits walking and talking with each other. I only knew it was the president-to-be by the back of his head. He was balding in a distinctive pattern that I recognized from his pictures. No one cheered; there was no commotion whatsoever as he passed down the street. Once passed, the crowd began to quickly disperse with a long line forming in front of some folding tables that had what I thought was some kind of petition to sign. When I asked what it was, I discovered it was for teachers. They had closed the town’s schools on the condition that the teachers and their families show up on the parade route and sign in to prove they had actually attended the parade.

A couple of weeks later I found myself in Oaxaca, Mexico to see another serious contender. I could not tell if he was a crook or not, but there was zero doubt that he was the candidate when he arrived. He was scheduled to give a speech in the town’s zocalo or central park. Again, I went early to get a good view. I was lucky I did. The place was flooded by thousands of noisy cheering supporters. Being taller than just about every other person in the crowd I saw the candidate, Cuauhtemoc Cardenas, arrive in a short line of cars about 100 yards away. He was immediately incased in a circle of bodyguards who had locked arms to keep his mob crowd of fans from ripping some souvenir out of his clothing. No rock star ever had a more enthusiastic mass of frenzied supporters. I knew then and there who would win or should win.

Some weeks later the election was held. I read that all of the state-run computer systems failed and when they were brought back online . . . well, I was glad and thankful that I was back home, where we would never allow corruption on that scale to stand. Right?

Near what was to become the end of my “walk-about,” I found myself in a sleepy tropical fishing village. It had no electricity, no phones, no roads to it. If you got there at all, you got there by boat. Surrounded by mountains, it was perfect for me, and so there I stayed under a palm-thatched roof with an open-air toilet and propane grill, in my cheese- clothed bed swinging from ropes, for a few dollars a night. I would return there several times over the years. But it was on that first visit, with thoughts of politics still eating away in my brain and American’s inability to see or deal with what politicians, their hacks, and the major parties were doing to it, that I got smacked with what would become my life’s work.

(New chapters will be added roughly once a week)

Richard Kimball, Vote Smart Founder

Sign up on my Blog at: richardkimball.org

or

Medium.com at: https://medium.com/@daffieduck2016