PISSING OFF YOUR FRIENDS

OK, if you are one of those reading this book, you might want to skip this chapter. For you, I fear it is a long sleep-inducing snore, but for me it was seminal, and so I must tell it all.

The elation felt during my first election victory was not duplicated during the second. I was thankful I won, and I celebrated with a lot of people who still strongly believed in me. But I now knew what being a State Senator was like and I did not think that I made for a very good one, nor did I think there were many others better. And a growing few were real stinkers.

The reasons I was a poor senator made me odd. I did not like giving speeches, wasn’t much good at wheeling and dealing and I found it difficult, if not impossible, to compromise a principle to achieve a necessary end – you know, that business of supporting a measure you didn’t like in order to get one that you did. In other words, what makes democracy work.

A legislature thrives, like any business thrives, by catering to the customers who come in the front door, and it was big money, in the form of paid lobbyists that came in the door each and every morning and hung around for the day. They are paid to get their bosses money or protect the money they already have. They know the legislation affecting their bosses’ interests better than any legislator and, unlike everyday constituents who rarely came through the doors, these lobbyists had the dough that fueled legislators’ re-elections. One day, some fifteen years after leaving the legislature, I decided to go back for a visit. Not a single member I served with would still be there but many of the lobbyists prowling the halls were the very same and the bureaucrats that ran the place where almost to a person identical.

Today, with term limits (something I once supported, like most frustrated citizens), no new legislators know what they are doing. Term limits dilute the citizens’ power to elect whomever they want, while also immensely increasing the power of lobbyists and bureaucrats who do know what they are doing. New legislators lean on them for everything, starting with directions to the bathroom on up to how a bill becomes law.

Blue collar types seemed to like me in politics, and I was a bit partial to them. I just liked people that work and produce, I was more comfortable around them and thus I naturally supported carpenters, machinists, steel and construction worker types, teachers, and of course fireman and policeman. They were always either sweaty, dirty, tired or all three at the end of their days.

I had discovered during that second campaign that the only time I would comment in front of a crowd was when I thought something important to say had been left unsaid and could be said quickly. One gathering of laborers fit those criteria.

Labor supported me as they do almost all democrats, for the same destructive reasons all selfish interests in society latch on to one side or the other…it is the gimme, gimme, gimme that all lobbyists for special interests represent. I do not mean to pick on labor alone here. Lobbyists are paid to represent doctors, lawyers, bankers, bakers, butchers, and candlestick makers at the expense of everyone else.

Labor’s political clout had been on the decline for some years, but they did support me, even when on occasion I did not support them, or in this case, even talk to them nicely. This particular election year gathering was of AFL-CIO members who came to watch a parade of candidates appear on the stage and plead for their support. It was the kind of ritualistic begging that goes on each election and degrades all involved. At this event each candidate was given 10 minutes to tell the Union why they thought they should get union support. By the time it was my turn, I had seen enough groveling, and I had something to say, thought it had been left unsaid, and I could say it quickly.

“This is Arizona. It is a Republican state with a Republican legislature, and they don’t like you very much. You are seen as liberal, and your public support will be a liability to me. If you know me as well as you might know a close friend or family member, you know I will support people who work, whether they support me or not. So be smart, don’t support me, endorse my opponent. His name is Joe Haldiman, and he may win, and if he does you will need his door open to you. In other words, if you think you are buying influence with me or that labor’s support isn’t being used against me, you can take your endorsement and stick it.”

It took me less than a minute; I walked off the stage to an audience silently gawking at me. But as I approached my seat, and to my astonishment, people began standing and cheering. People who work can be funny that way.

The me, me, me of lobbyists knows no bounds. They are “just doing their job” they like to say, but their job is dragging legislatures from sea to shining sea into the grimy selfishness of me, me, me. In that work they would play a big part in my long brewing and now imminent rebirth, at the end of my second term.

It did not matter if a candidate had been absurdly but successfully labeled liberal or conservative. If an organized selfish interest on either side helped you get in, deliverance of the goods to that interest was expected.

During my experience in the Twilight Zone of my re-election, and oddly during my divorce, one of my biggest backers was the National Organization of Women. Again, by sheer coincidence, they liked me because of beliefs I already possessed. Long ago my mother and Lacy Scanlon, my grade school love wish, taught me that women were a superior gender.

Guys have been running the show since human time began. As for women, well, we want their friendship, loyalty and of course their bodily submissions. They serve in every imaginable way without a fair or even reasonable stake in life.

Most men are so blind when it comes to women. They fail to recognize or simply accept and expect that women will be of service to them. That is why women are not fairly paid or promoted, why they are given inferior health care, constitute the majority of the poor and are abandoned by the millions with our children. Open a door for them? Sure! Adjust a chair as they sit? Sure! What a cheap price it is we pay. And if they object, well that is why one out of every four housewives are abused at home and 600 a day are raped or sexually assaulted.

Superheroes defend women and children, legislatures do not. And they don’t because …… well, …… I really don’t know why. There are more women than men, they have the vote. I just don’t get it, but I am damn glad I am not a woman, and it is a good thing for men that I am not a woman. For after 250,000 years of this shit, I would surely support all abortions, both pre and post birth, as long as they were of the male gender.

I was the sponsor of the Equal Rights Amendment, a now long dead effort to ensure women equal protection under the constitution. Protection they had historically and statistically lacked since the very moment they tricked the rest of us into eating healthy apples. They had a little difficulty with my occasional remarks against some abortions since I did not feel I could competently divine exactly when a conscious life began but they were willing to overlook it.

But women’s groups behaved no differently than organized labor unions, oil interests, bankers, bakers or those candlestick makers. Anyone of which makes a good representation of how tortured and convoluted representative government can become.

Once money from selfish interests is accepted, the bargain is struck — you have a friend, they have a friend, and it is these friendships that make such a mess of our struggle to self-govern. It is as simple as understanding that if you give $50 tips rather than $5 tips you will get a better table.

Now this is as absurdly convoluted as it gets: The National Organization for Women slammed me for sponsoring the ERA. They had decided on a strategy that would demonstrate a lack of support by the “insensitive” Arizona legislature, to anger contributors out of more money so they could then spend it in other states they thought had better chances of success. It seemed not to occur to them that this Machiavellian scheme to cast the legislature as completely insensitive in order to raise revenue was disingenuous. It was also unsuccessful, and the Equal Rights Amendment, that great equalizing legislation of the women, largely by women, for women perished from this earth.

I was beginning to hate being in public office, not just because of those whose views I often opposed but because of those whose views whom I had often supported. Elected representatives thoughtfully considering the various courses that might be taken on problems facing society seemed non-existent. There was no real debate or any sort of open communion on the roads that might be taken on any contentious matter — just an endless process of deals, where blame, brag and accusation swirled in endless conflict over some morsel of advantage for one party or the other.

I regretted that I was now obligated to serve another two years and knew I would never run for the legislature again and was happy to just quietly live out the term. But happy and quiet was not to be. It appears I was primed to blow a gut and be the talk of the town.

The weeks, issues and votes went by, including one that called for the biggest tax increase in the state’s history. It was a gas tax designed to build better roads that would be collected primarily from the Ford and Chevy owners of the world. Roads are very expensive largely because they need to withstand the enormous pounding they take from the tonnage on eighteen-wheeled semi-trucks. If all you had on the roads were Fords and Chevys, they would essentially last forever.

Anyway, the tax was designed to be little more than a subsidy to the trucking industry, so I voted no. My argument seemed logical to me: The people creating a cost and receiving the benefit should pay that cost, in this case trucking interests. But my old friends in labor who wanted road building jobs, bankers and realtors wanting more growth, truckers, of course, and just about every business that wanted more people and what they buy had their thumbs in the pie and opposed me. It was not unusual for those interests to feel that way and not unique for me to be on the losing end of a vote.

However, this legislation, strongly supported by a Republican controlled legislature and our Democratic governor, would be forced into a second life at the hands of thousands of angry, vengeful citizens who saw no common good in any tax.

The bill and the events surrounding it would be a life-shaping experience for no one but me. I would take the silent, invisibility that was me, spanning back over the decades and make up for it in one foot stomping blast of words that would not be silenced for 5 days and nights. That “another day” of my youth was about to arrive. I was 31 and about to be born again—and insist on making my life, if not worthwhile, at least not worthless.

The story actually starts in 1912 when Arizona became a state and adopted an extraordinarily progressive and unique set of citizen protections in its Constitution. One was the citizen’s right to stop the legislature from imposing any law they thought a bad idea, called a referendum. It required an ungodly number of petition signatures to do it, but if citizens chose to go out and get them, they could then vote on the matter themselves and tell their government to go to Hell.

Well, for the second time since statehood the citizens of Arizona looked at what the governor and legislature were doing and did just that on the gas tax bill. They organized and got the needed signatures requiring their government to put it up for public vote. I had played a small part in getting those signatures, but the real leader was Terry Goddard, a good, decent, honorable fellow, close friend and son of a former governor.

This caused a great deal of shuffling amongst the well healed powers of the state. The banks, unions, realtors, developers of every sort, weren’t going to get what they had paid for with their lobbyists and political contributions if citizens were allowed to vote the gas tax increase down. So, they decided to sponsor a secret meeting, not at the people’s capitol building, but in a private meeting on the 25th floor of a bank building in Phoenix. There the governor and legislative leadership of both parties would hold a private conclave without pests like me, the public or the media, and decide what to do about the ignorant masses who didn’t want the wall-to-wall paving of Arizona.

Their plan was deviously simple: The governor would call the legislature into a special session where they would pass a new gas tax bill that would do the exact same thing as the original bill that the citizens had stopped. Only the new bill would have a different bill number and title. And for this new bill they would put enough pressure on legislators to pass it with what is called an Emergency Clause, forcing it into effect before citizens had any time to gather the signatures necessary for another referendum.

HERE

I got wind of the plan and the secret meeting. The arrogance of it was ludicrous, I thought. “They will never get away with that!” I told Terry. They did not invite me to the meeting, which was fine because they did invite Terry. He and I got together and devised a sure-fire counter measure. A piece of cake we thought, there was no way we could fail to stop them, we would embarrass the whole shifty group. He would go home, get dressed, and let me know when he went into the meeting and then just sit and listen politely to what they had to say. I would hit the phones and contact all of the media, tell them of the secret meeting and its location. When the media arrived Terry would simply step out and expose the effort to trample the State Constitution and the people’s will. Game Over! He would be the people’s hero.

It was a slam dunk, Terry let me know when he went into the meeting, I went down to have a visit with the capitol press corps and made my calls. As expected, the media stormed the bank building. The easy job, my job was done. I patted myself on the back and waited for Terry to return with their heads.

An hour later (it apparently did not take long), the Democratic majority leader, one of the meetings sponsors, came prancing down the hall. I gave him a big snooty smile and said, “I guess it didn’t go so well.” He went striding right past me and flipped a chuckle into the air, “You must not have your television on.”

The smile dripped off my face. It just couldn’t be. I ran into my office and turned on the tube just at the right time. There was my was Terry, my buddy, who on behalf of the Governor and the legislature, was announcing that he thought the new legislation great and would help lead the charge for final passage of the Gas Tax Bill.

I no longer cared about the damn gas bill, this was now legalized, corruption at its worst, a theft, a trampling of what was still right with the world. No one knew the truth of it, no one to expose the truth of it, no one but me. I could feel my father’s eyes riveted on me and saying, “Kimmy, it is now or never.”

I was numb. I had never had a friend, someone I trusted, even admired, turn and do such a despicable thing. Was everyone on the take? What had Terry sold out for, what did he get? I didn’t want to believe it, there must be some explanation, something I didn’t see, didn’t understand and Terry would surely show up soon and tell me what had happened. But no, Terry didn’t show up, he never showed up. . .well, not until the wee hours one night 10 days later to sit in the gallery and watch me struggle to stay awake on the Senate floor.

The rumor mill went crazy. What deal had the governor’s son gotten? I certainly didn’t know. I was concerned with one thing: was there anything I could do to stop it?

The governor called the Special Session the following week, the Gas Tax Bill would be introduced, and I had something to say. As the Senators filed in, I was sitting at my desk and after the Secretary read the bill, for the first time I reached for the microphone to speak. I simply said, “In the three years I have served as a State Senator I have not taken your time with a single speech in this chamber, but if you do this thing, you will hear from me. I will give you three years’ worth in a single standing,” and I sat down. The senator sitting next to me stopped reading his newspaper and asked, “Did you say something?”

That night I didn’t sleep. I was sad, angry, and very worried that I wouldn’t fight, that I would find some excuse to just let it go and remain quiet and hidden in the dark. I knew if I did remain invisible it would leave a hideous scar, even if no one could see it but me, along with the knowledge that my life really wasn’t worth the living of it.

Late that night I called a few other Senators I thought might be willing to fight with me and asked them to meet me for a very early morning breakfast. Then I spent the night walking up and down the same streets I had walked so many times before, filing past all the people’s homes that I had visited during my campaigns, going over and over in my mind what I might say the next day when the fight began. At 6:00 A.M. I walked into the nearby Denny’s to meet with the “Breakfast Bunch,” the other Senators I had called. I had not slept but I wasn’t the slightest bit tired.

I sat down. There were only six of us, but it was a start. They all talked outrage, but they just weren’t as crazed as I. One, Marsha Weeks, intended to go on vacation that day. Another seemed to see a filibuster, the only stalling tactic available, as a good press opportunity. But two others seemed spirited and ready to audition with me for the key role in The Man of La Mancha. At the morning session when the Gas Tax Bill came up, I would ask to be recognized by the President of the Senate and start: speak as long as I was able, then, just like in a relay race, yield the baton or in this case control of the Senate floor to one of the “Breakfast Bunch.” They in turn would go as far as they were able, pass it on to another, and another and eventually back to me. And so, we would go until we had shaken things up enough to stop the vote or simply run out of steam. We hoped we could keep it up for a day or two until citizens had a chance to see in the news what was happening and get a chance to make a fight of it all their own.

Our breakfast meeting ended, I went home, took a quick shower, got dressed, and entered my Senate office 30 minutes before the morning session would begin. The Senate was called to order, and I was about to blab like no one had ever blabbed before. I had thought about what I would say for a long time the night before and thought it was important—if to no one else, it sure was to me. I had asked my secretary to record it and had set up a machine to do so under the speaker in the ceiling of my office. I knew I would want to listen to it later to make sure that I said what I meant to say, what needed to be said.

As I took my Senate seat, I noticed that the gallery was filling up with the usual lobbyists and guests but also with an unusual gathering of Senate staff, pages, janitors, and secretaries, including my own secretary, who it turns out never punched the record button on the machine I had set up. People were in the gallery who were never there–people around the Capitol knew something was up. I took the microphone with something to say for the second time in two days and three years. I do not remember precisely what I said, and I am not willing to try and reinvent it over forty years later. My short two or three minutes dealt with people, their struggle to self-govern, responsibility and the dignity of the Senate and was effective enough to have a few members slump in their seats and a few out of place hand claps from the gallery.

After some moments of silence another Senator stood up in an effort to defend the plan created in the bank building meeting. I had expected this and had also thought of something to say should someone stand and disagree with me. My response was neither mean, nor abusive but it was so blistering and humiliating that he slunk off the Senate floor. Those who were part of the secret meeting, I thought might also have something to say but were all suddenly distracted, looking away and backed off their microphones as if they might bite.

The Senate President thought it a good time to take a recess. I walked off the Senate floor where a number of Senators gathered around me slapping me on the back, one older member said, “Son you need to speak up more often, that was worth every day of the time it took you to say it.” Another Senator, one of my Breakfast Bunch and a long-term Senate veteran said, “They were the most eloquent remarks ever uttered on the Senate floor.” When I got out in the hall some of the people who had been listening from the gallery came down to thank me, even the Senate Minority Counsel said, “I thought your first remarks were brilliant but then when you took that other Senator down, I almost screamed with joy.”

Now normally I would feel elated at such wondrous compliments and slaps on the back, and now, on reflection, I feel exactly that way. But I did not then. I was completely riveted to my mission. I was going to beat them.

Thirty minutes later the Committee of the Whole was gaveled to order. It was clear that trouble was coming so all other legislative matters were disposed of, putting the Gas Tax Bill up for debate. It was Wednesday morning just about 10:30 a. m. when I was recognized, stood and grabbed the microphone for the third time, and this time I would not give it up.

The first half dozen hours went by easily, I never ran out of things to say. When I really wanted to make my point, I would simply read off a few hundred more names of those citizens struggling to govern their own lives, who signed the petitions that were now stacked on my desk.

Eventually I had to go to the bathroom, and I nervously turned over the microphone to Senator Alston, the most loyal member of the Breakfast Bunch. She continued to read the names into the night as I sat there and kept her company. Then I took the wee hours shift. By midnight the gallery was down to just two or three diehards, a few members of the press, the recording secretary, a page and one other Senator unlucky enough to be selected to sit as the presiding officer. Should I falter, he would gavel me out of business. My other fellow Senators had all departed for home hours ago. I just stood there and kept reading those names.

When the morning paper hit, it was not supportive, its fake decorated military leader made sure. And since almost every other news outlet was “rip and read” (meaning they had no staff and just regurgitated the news from the major paper), the point of the filibuster got zero coverage.

That wasn’t a total surprise, but the following day people started showing up and sitting in the gallery. Radio station KOY came in and set up microphones and broadcast “the filibuster that would not end” live on and off throughout the day.

This picked up my spirits because I knew someone had to be listening. As an additional moral builder, it just happened to be the same radio station where my mother had once had a radio show back in the day when my father was the Senator, and she was trying to preserve some of her Hollywood dreams.

On Thursday night I still did not feel any end to my energy, and as I spoke on, I marveled at the fact that I could stay awake so long. When one of the Breakfast Bunch would relieve me, I would get something to eat, use the restroom or check with my office for messages and then come back and sit until it was time for me to take over again.

On Friday various appeals were made to get me to stop. Some were from friends actually concerned for me, but most of the appeals came from those who had been in the “secret” meeting and just wanted to get me out of there and go home.

Naively, I assumed other media would eventually investigate what had happened, about the bank meeting, Terry’s sell out, and explain how the Gas Tax issue had been trumped by the vastly more important issue of circumvention of constitutional intent. They did not.

As I stood on the Senate floor hour after hour, the leadership worked the press. Few in the media understood what had happened but some sympathetic stories began to leak out. Thousands of calls started pouring into the senators’ offices demanding to know why the hell they were shoving this tax increase down citizens’ throats.

The pressure was on. More secret meetings were being held in the Capitol’s back offices. Votes needed for the Emergency Clause that would strip citizens of their right to do another referendum started to collapse. Knowing that, would get me through another night.

On Saturday morning, I realized I had not been in a bed since Tuesday, I had not left the Senate floor except for bodily requirements since my Wednesday speech, and I was beginning to feel it. When one of the Breakfast Bunch would come to relieve me I would go to the back of the room and tilt a chair against the wall, close my eyes and try to sleep, but I couldn’t. I was convinced that if I did sleep, something bad would happen. About noon Senator Alston came, asked to take over and insisted that I go look out the front windows.

Down on the mall in front of the Senate Building a group of demonstrators had arrived and were setting up tables, passing around new petitions, carrying placards, and doing chants about taxation without representation.

I wanted to go down and tell them to forget the tax bill, the issue was now far greater, that their representatives, corporate leaders, and unions were doing a hat trick that would, if successful, turn them into chattel. I wanted to get them to leave the Capitol and go stomp around in front of the Senators’ homes because that is where they were. Senator Alston, me and the unlucky lottery loser selected to preside were the only Senators at the Senate that Saturday.

Senator Alston, who I adored beyond her politics and support, was right. The scene out front was a big boost to my spirits.

There is no place deader on earth than a state Capitol building on a Saturday night. Generally, you could go into any state senate chamber in the country, fill it floor to ceiling with actual bull shit and no one would notice until it opened for business the following Monday. The complete deadness of the place, no one in the gallery, no press, just the legal minimum sitting in the presiding chair, made me begin to doubt myself. The lack of sleep was getting to me in a way I had not expected, it didn’t make me feel sleepy as much as it made me feel punchy. It reminded me of my college days getting sloppy headed drunk but without the morning after hoping-to-die stuff.

Sometime late into Saturday night I was analytical enough to notice my sentences were not holding together very well and sometimes I couldn’t remember what I had just said. The presiding Senator, for whom I was clearly ruining a weekend, leaned over from his chair above the Senate floor and with a mixture of concern and hope for a middle of the night finally asked if I was all right.

His questioning of my stamina made me feel indignant, flushed me with new-found energy and I began speaking loudly and clearly again. As he shook his head, I swung around to say a few words to the empty gallery, only it was no longer empty. There was someone sitting up in the shadows off to one side.

Leaning forward in a gallery seat, with his elbows on his knees and head in his hands was my good friend, the former Governor’s son. I said nothing to him, I just turned around grabbed a handful of the petitions he had gathered and championed for the people that had trusted him. I read them very slowly, one syllable at a time. I imagined that each one was like a dart to his heart, but when I turned back to the gallery he was gone.

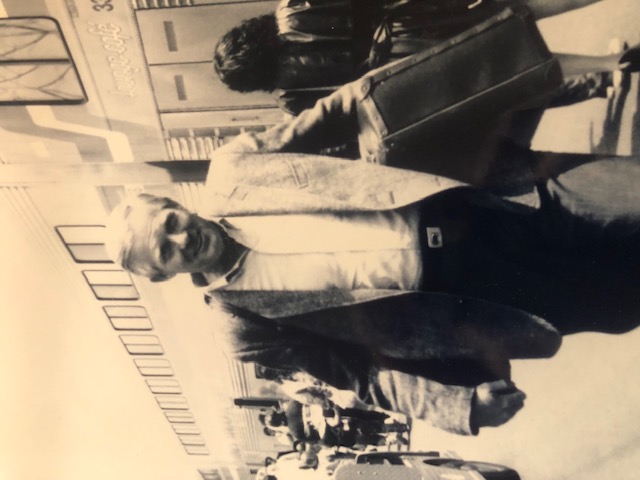

Early Sunday morning I was having a little trouble thinking clearly again when one of the Breakfast Bunch relieved me. He said, “Don’t worry, I’ve got it.” I hadn’t been outside of the capitol building in four days and decided to take a short walk on the capitol grounds. I walked out the front door and around the corner, took off my shoes and socks and walked through the grass so that I could feel the tender shoots punch up between my toes. As I approached some trees I looked around and realized I was completely alone, I was invisible again. And then suddenly, out of nowhere and for reasons I can’t explain because I really don’t know, I began to sob.

At about mid-day on Sunday members of the Senate started to show up. I didn’t know why, and was too spent to really care, but I should have.

The approach was made in the interests of my health. “We want to get you a doctor, we need to get you a doctor, let us call a doctor,” the Democratic Minority Leader and key member of the secret meeting said to me. “NO, I am fine,” I said. “Well at least take a break, go home and get some sleep, you have to rest,” he insisted. “NO, I am fine,” I said. “Listen, I am the Minority Leader. You helped elect me as the Minority Leader of our party. I give you my word that I will not let anything happen while you go home and get a few hours of sleep. We are all very worried about you.”

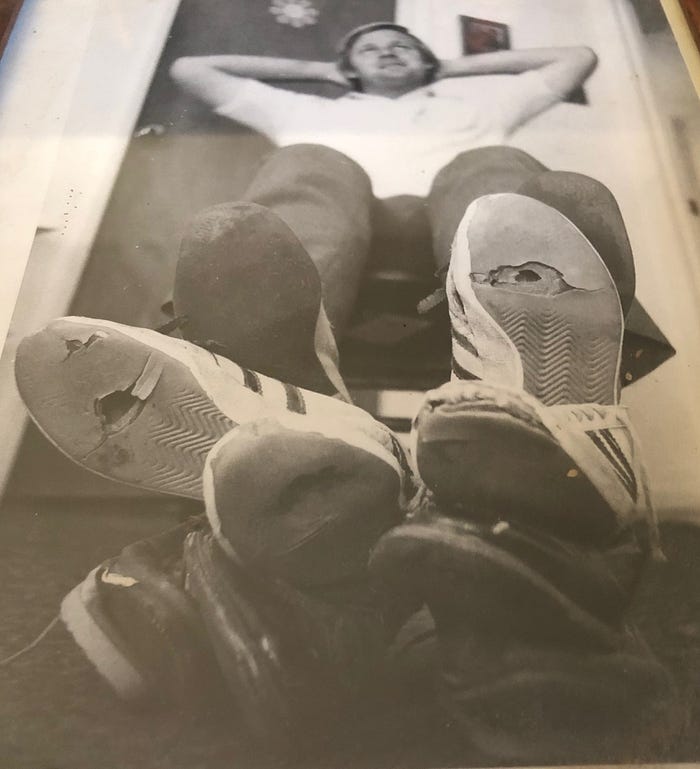

I thought about it, I knew that my supporting cast of Senators wanted to end the filibuster the next day during the Monday session and let the votes fall where they may. I knew that I couldn’t go on forever. And I knew that no matter how clean and fresh I felt when I started, people had started standing a measured distance away from me. I stunk!

I turned it over to Senator Alston, that closest member of the Breakfast Bunch. And on the promise of the Minority Leader, I drove the five miles home, hopped into the shower and flopped down on the bed. Almost immediately I sensed something was not right and then remembered with a start, that when Senator Alston had done her turn, she would turn it over to the weak link. He was the same Senator that had told me days before that my remarks were the most eloquent he had ever heard, but he was also a close loyal friend of the Minority Leader. The shower had revived me a bit and brought some of my senses back. As I raced to my closet, I knew I was in trouble. Why had some Senators started showing up on a Sunday morning? I was out the door like a shot and running into a Senate chamber still trying to tie my tie.

Turns out that during that hour I was gone the leaders pressured my weak link and got him to agree that when Alston passed the microphone to him, he would stop the filibuster.

An hour later and it would have been over. My weak link had cut a deal with the leadership, he would pass the microphone over to the opposition and the filibuster would be ended. My sudden and totally unexpected appearance stopped him. Embarrassed, he left the Senate Floor, and I was gritted to make to Monday.

As it turns out some of the other Senators had not shown up just for the killing—at least not willingly. They wanted deals. They had been trying to cut deals for days and every once in awhile one would come out of a meeting and look upset. I wouldn’t understand it until the media broke a few stories.

The votes had started to collapse, and the leadership was in a full-court press, ready to break arms and threaten constituencies and political careers in order to keep the big money deal hammered together. There was the story from the angry legislator upset about the “unheard of” pressure tactics, another from a Senator who claimed that they threatened to withhold money from his reelection campaign if he didn’t stay the line. Sicklier was the story threatening a legislator’s constituents with the loss of a bridge needed for fire and police protection.

If the leadership didn’t get two-thirds of the Senate, meaning most of the majority and a good portion of the minority, they couldn’t pass the bill with an emergency clause. Without that emergency clause the bill was worthless; citizens were angry and getting the necessary signatures again? No problem. A lot of Senators took heat that day.

At 10:00 a.m. Monday morning, five days after it had begun, it all came to an end. There wasn’t anything left to do. All the attention that the issue was going to get had been gotten, all the tactics that could be employed were done. I relinquished the floor. It was time to call the vote.

It was unclear how it would go until the very last vote was tortured and locked. Many Senators tried to explain their votes when they were called upon. Those who voted YES broke into three categories: Those who had attended the bank meeting or represented safe districts were sheepishly silent. Those who were not from safe districts tended to apologize for their yes vote and the manner in which the issue had been mishandled, manhandled and coerced. Others were clearly pained by events and even made remarks in opposition to the measure, and then inexplicably voted for the bill.

Those of us who voted NO, said little and anxiously kept track of the tally. It came down to a single vote and the Senator who cast it, clearly under enormous pressure, began with a blistering attack against the leadership, the bank meeting, and the way the legislation had been managed. Then she hesitated and angrily barked, “I vote YES,” and stomped off the floor.

Luise Gonzales, me, Lito Pena, and Lela Alston

The Breakfast Bunch minus the traitor and vacationer.

A researcher would later tell me it was the longest filibuster anywhere by anyone. I’m not sure that is true, but I was grateful to think it. I had lost the vote but as odd as it may sound, I was fine, better than fine. I felt selfishly good about myself, if not for all those I had failed. I had come out of the dark, was visible and convinced that I had fought as hard as anyone could fight. I had done the right thing. I had lost but felt that my life might one day find some way to become worthwhile after all.

As I walked off the Senate floor, I was asked to meet with the media who had all gathered in the Republicans’ caucus room. As I walked in and stood at one end, the television lights came on and I was bombarded with questions. While talking, I noticed at the far end of the room another, even larger group of reporters had gathered around some fellow. He wasn’t a member of the victorious leadership, nor any member of the legislature, nor staff, or any government figure or person I recognized. When I asked a reporter who it was, he was surprised and said, “Why that is the guy who sponsored the private meeting you’ve been trashing these past five days. He’s the Bank President.”

(New chapters will be added roughly once a week)

Richard Kimball, Vote Smart Founder

Sign up on my Blog at: richardkimball.org

or

Medium.com at: https://medium.com/@daffieduck2016

Comments closed