When former Texas governor John Connally took a private jet in 1980 to convince Iran not to release the hostages, the Carter Presidency was done. Such was the underhanded ugly, in old time politics.

Carter, the antithesis of what is to come, thought we should not only be the top military power but also “the champion of peace, champion of human rights, champion of the environment and the most generous nation on earth.”

Carter knew that knowledge was the only real source of human success and thus created the Department of Education.

Carter knew that bringing adversaries to the table and convincing them peace was a mutual advantage, might bare fruit and thus the Camp David Accords, which won for Begin and Sadat the Noble Prize.

Even out of the Presidency Carter spoke truth to power as when he was amongst the first to say, “There was no reason for us to become involved in Iraq,” or when he suggested we cannot be peacemakers if American government leaders are seen as knee-jerk supporters of every action or policy of whatever Israeli government happens to be in power at the moment. That is the essential fact that must be faced.”

But mostly I loved Jimmy Carter for his devotion to us after his Presidency, his tireless journeys all over the globe to promote peace, health and justice and his passion for the less fortunate here at home.

All former Presidents retire, comfortably cocooning in their former glories. Not Jimmy Carter, my hero!

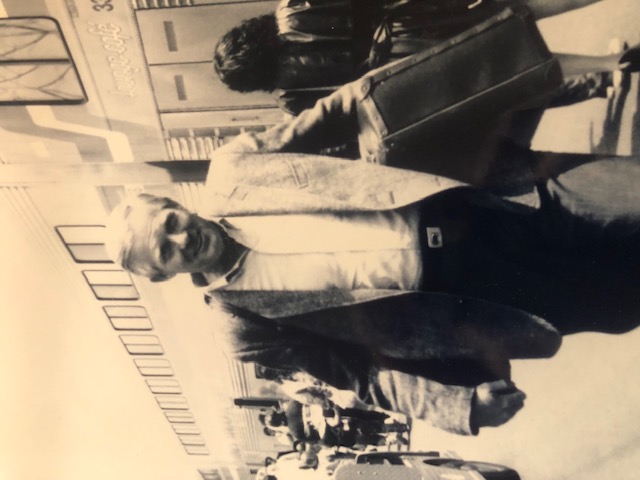

Twice my boss, first as my boss’s boss when I worked for Walter Mondale and second as a founder of an organization called Vote Smart where I was dogged on his example for 35 years as its President.

Richard Kimball

Sign up on my Blog at: richardkimball.org

or

Medium.com at: https://medium.com/@daffieduck2016

Comments closed