I was sitting in my highchair looking out the window at my dad’s Packard when she set a bowl of soup in front of me. It had to have been the Campbell’s kind. I could see the bits of drowned vegetables and occasionally flaking cubes of chicken, but what caught my eye was the teensy weensy, perfectly round, shiny bits of oil that floated on the top. I wanted to know what they were but was not yet far enough along in life to manage an inquiry. I was still having enough trouble managing a capture with my spoon.

She stood behind me that morning, all round and dressed in white, but black. Her name was Essie, our maid and cook. My mother did not have her help often and I do not remember much about her other than the chicken she fried, great chicken my older brothers later assured me. Chicken that our mother, the German antithesis to fine dining, could never duplicate.

A year or so later, I visited Essie’s house. She lived in a home very unlike our own. My mother was bringing her some Christmas gifts, and I happened to be in the back seat.

We lived in a big house. I didn’t know it. We lived in the nicest neighborhood. I did not know it. As we turned onto Essie’s street the houses became tightly jammed, any half-dozen of which could have easily fit into our front yard. As best I can recall, there were no driveways, and the yards were all barren dirt with a few broken toys, flat balls and scraps of various objects scattered about. Inside, where doors would be, there were hanging sheets and there was one stuffed tattered chair. The walls were unpainted with one wall having a large chunk of missing plaster which commanded my attention because I could not imagine the purpose of the wooden slats that were now exposed underneath.

Above all, I remember that Essie had a family; this was a very big surprise. It never occurred to me that she would be a wife, have children, a home, a life. Essie was just our maid.

I did not feel sorry, have any sense of pity, I was not old enough to know such things. I only recall being confused, wanting to leave and being happy that my parents chose not to live that way.

I would not see those kinds of living conditions again for 15 years, not until I stood in the dump three of my college buddies and I could afford and used to eat, sleep, drink, and smoke dope.

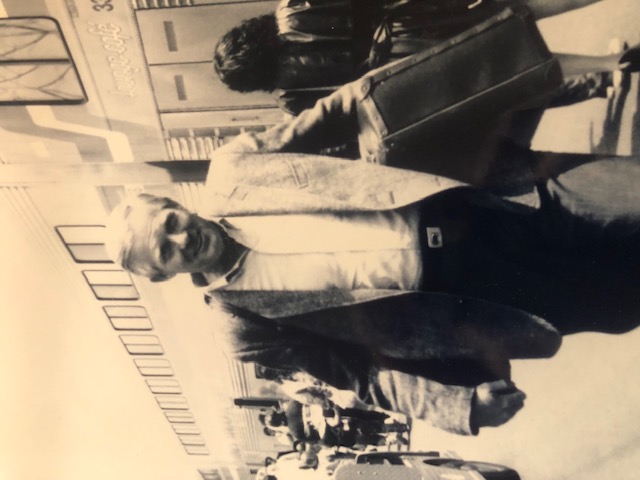

Richard Kimball

Sign up on my Blog at: richardkimball.org

or

Medium.com at: https://medium.com/@daffieduck2016