BURNING DOWN THE HOOD?

It is impressive to me that my three brothers and I survived adolescence and continue to survive a half century later. In Mom’s lonely years, after Dad died, her sons managed to trash four cars starting with her dream car, her baby blue ’57 Chevy convertible that couldn’t see red lights and ending with me taking her dream’s diminishment, a baby blue VW bug off a 20 ft. cliff. There would be some hard drugs, a lot of booze and a stint in a Mexican prison. Those shorts are not unique or even representative of the worst things my brothers and I did and would do.

But this book is not about us, it is about Me, Me, ME! so let’s stick to the point and go back a few years one more time.

My mother was fun, tough but far less harsh than she should have been. She was the family disciplinarian even when Dad was alive. With Dad you simply feared his disapproval, which was as bad as the world could get for me. With Mom it was a too rare a hand, switch, or belt which on one, forever-to-be-disputed occasion, caused a few deserved but unintended “welts”.

In fourth grade, I thought she was unfair, too tough, but now in reflection it is a marvel that she did not end her misery by just end us all.

The “welts” incident started when my best friends Stevie Bogard and Butchy Becker were playing in the “game room” of our house where my brothers and I had our toys, balls, childhood drawings, and various knicknacks of childom. It was designed and still occasionally used as a place for adult entertainment. It was quite large and everything in it matched: knotty pine walls, ceiling, built in matching knotty pine bar with a knotty pine couch, knotty pine poker table and knotty pine bar stools.

Butchy saw it first, folded and tucked neatly behind the bar’s sink, a $10 bill. It was early December, and I knew the tradition. Each Christmas my grandfather, who couldn’t travel and join us for Christmas sent $10 to buy our Christmas tree. Mom tucked it behind the bar until it was time to make the big buy. But Butchy and Stevie got so excited with the treasure, I got excited too. Treated as treasure found, it was instantly seen as free money, now our money.

After all, I did not actually see Mom place the money there, a crack in the sink was such an odd place to put such a treasure. YEAH! That’s right Butchy, you found lost money, BIG MONEY!” Ten dollars in the 50s, is about as rich as three kids can get.

The negotiations started immediately:

Me — “Sure you found it Butchy, but it is my house, my bar, my sink, so it is my $10.”

Butchy — “OK! We’ll split it”.

Stevie- “Hey, that’s not fair, what about me, I was here too.”

Me — “What are you talking about, you didn’t find it, and this isn’t your house. You don’t get anything”

Stevie — “That’s not right, let’s ask your mother.”

Stevie, who became a very good lawyer as an adult, always had a knack for ending an argument with just the right line.

On the way to the Five and Dime the discussion was all about toys, a new football, a whole bunch of trading cards with gum, or . . . “I got it,” I said, “the toy to beat all toys. We have enough money here to buy each one of us a Zippo cigarette lighter.” The idea was an immediate hit, not because we smoked, at least not yet, but because we were fascinated with what all young men of seven are fascinated with, FIRE.

We were just smart enough to know that the store might not want to sell lighters to kids, so we devised a brilliant and as it turns out successful plan. Since Stevie’s handwriting was clearly at a crude stage and I could barely read, let alone write, we decided Butchy would do the honors. As neatly as he could, which was pretty darn good as I recall, we wrote out: “I hav givn Kimmy $10 to by three liters — (signed) Mrs. Kimball.” I remember that the fellow at the drug store looked at me a little funny but didn’t seem to mind selling us the lighters or that my mom was illiterate. So, with lighters in hand, off we ran toward the arroyo and into neighborhood history.

The arroyo was a dry four-foot-deep rut in the neighborhood landscape that had water in it maybe six days a year. It ran right by our house and was perfect for hiding our mischief. It was sheathed in a thick forest of mesquite trees and at this time of year, tall baked brown grasses.

With all the life-molding first time experiences that would come that day, it wasn’t Mr. Franklin, our neighbor that was first to see the smoke billowing over the neighborhood and did that spectacular rendition of Paul Revere. Nor was it the distant approaching sirens that converged on the scene, not even the odd smacking sound my mother’s lips made when she heard it was me, that sticks most clearly in my mind. It was the speed at which a little Zippo could turn solitude into Armageddon when it touches a few blades of dried grass in a breeze under a forest of parched desert trees.

I can’t remember what happened to Stevie that day, I wasn’t able to see him for a month, but I did hear from my brother about Butchy, who clearly had the best strategy; he ran into his house and immediately bolted himself in the bathroom. After considerable time, his parents finally managed to convince him that he would not be put to death, and he dared to unlock the door.

I, on the other hand, would be put to death immediately. My mother, having struggled with this odd, stupid, and now clearly-dangerous child for some years, cracked. She took me back into what we called the maid’s room, although we had not had a live-in maid for years..

Forced to explain what we had done and how we had done it, she then told me to take off my belt. The fire was not what upset her, it was the “Thou shall not steal” stuff I was about to get it for. She gave me one good whack for every dollar I took.

In time what happened would become a humorous contention between my mother and me until her death 50 years later.

Was it ten good smacks with my cowboy belt or not? Now this is important because in the ’40s and ’50s the world had yet to be completely overrun with synthetics. Belts were leather and if you had a real kid’s cowboy belt it would very likely have a metal tip on the end to keep it from curling up on itself in the wet and grime of kiddom.

Never mind that I deserved to be euthanized, she would swear over the years that she would have noticed the tapered metal tip and never used such a thing. I, on the other hand, remember proudly showing the kids in school, with a certain manly pride, the lightly-matching pointed marks on my butt.

Metal tipped or not, I got the best of it. Kids, once adults, are forever blaming their mom’s for imagined errors in their upbringing. The “welts” from the fire of ’56 would become my most effective weapon as I needled my mother for the next half-century, even knowing I had gotten the best of it. I got the $10, the lighters (she assumed the Fire Department or someone else had confiscated them — they had not), and my exaggerated stories about “bloody welts” from the metal whip I was smacked with. The stories were always good for effecting motherly screeches of remorse and denial.

In the end, her defense of all my and my brothers’ transgression was that look of exasperation that every mother successfully past her child rearing duties can appreciate and that shirt she enjoyed wearing emblazoned with, “IT’S ALL MY FAULT”.

New chapters coming once each week — Full book thus far under THE MIRACLE OF ME / autobiography of a nobody

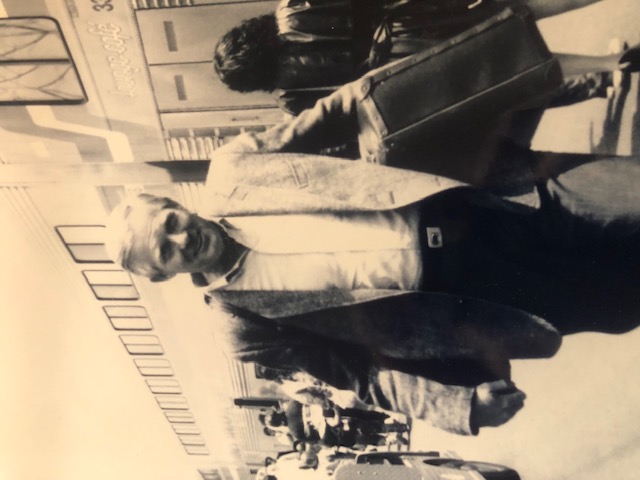

Richard Kimball — Vote Smart Founder

Sign up on my Blog at: richardkimball.org

or

Medium.com at: https://medium.com/@daffieduck2016