EINSTEIN AND ME

Despite the trials that stick out like blades of grass on a finely mowed lawn in my childhood, I had a wonderful young life. My recollections are filled with an endless series of seemingly undramatic events, smells, tastes, feelings, a wonderful never to be replicated sense of freedom to dig in the dirt, build a fort, climb a tree, do some good long-distance spitting, or just fart, that you will never know again as an adult. It was a world of excitement filled with what now appears to be insignificant things but then were wondrous and fun. Even now, more than a half century from my childhood, every rare, wonderful once in a while, some unique mixture within a moment will plunge me into some distant memory of my youth when the mixture was precisely the same. It can be something as simple as the angle of the sun sparkling off a puddle of rain, the warmth and color of the sky at that moment in the day, the taste of dirt picked up in a gust of wind, the smell of a broken branch or some crushed fresh leaves in my hand, the sound a bird makes when you have crept so close you can hear the flap as it flies away, the jarring shock of a thunderbolt when you were told to come inside, or the rich scent of a freshly mowed lawn at the park. At the right receptive moment, almost anything has the potential to let you close your eyes and send you back decades when you were tasting, smelling, feeling, hearing, and seeing it all for the very first time.

School, church, neighborhood friends were important, but the real action was at home. I have been fortunate to come into contact in my adult life with a number of wealthy, famous, powerful people but none ever rocked me like my brothers Billy, Bobby and Johnny.

It would be so much more entertaining to review the childhood behavior of my three brothers than that of my own. They were so much more adventurous in life than I. In almost every measure that you could make of a child I was more cautious and less courageous than my brothers.

My adventures seemed always unplanned and unintended. If I had a hazardous harrowing experience it was inevitably a mistake. Like the first time I unwittingly slammed against death’s door and tried to shove my family through it.

It started when my mother put in a swimming pool. She did it at about one thousandth of the cost of our neighbor’s pools which she had no desire or ability to compete with. Instead, as only our mother could or would, she paid a truck driver to haul in a round metal cattle tank. As cattle tanks go it was a large one about 10 feet wide and 2 1/2 feet deep. She then stuck a hose in it, which we let run endlessly.

No pool anywhere on the planet was ever such a hit. No one wanted to swim in the parentally supervised, take a shower, don’t get dirty, crystal blue water affairs of our neighbors. We were forever removing the bottom metal plug and refilling ours with fresh water to ready another day’s duty. The area around the cattle tank was a mud bog of infinite possibilities where the muddy water closest to the tank was simply a slimy extension of the “pool” itself. The mud a little further away was perfect for a style of gluey bathing all its own and the mud furthest from the tank brought the kind of impromptu heaven known only to a hot desert childhood – a far more colorful version of a snowball fight.

The tank itself was a true wonder. With just a couple of kids it could be instantly transformed into a cleansing vortex of what appeared to be chocolate milk. My mother had created the nation’s first water park and not one of my neighborhood friends did not prefer it to their own chlorinated, parental law-laden show piece.

The only fascination I had with the other neighborhood pools had to do with what creatures might be trapped in the gutter or filter. More importantly, what was with all those cleaning chemicals emblazoned with the skull and cross bones stamped on barrels and jugs of stuff? Ah, the mystery of the innocent-looking fluids and powdered chemicals.

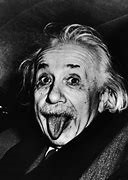

My brother Bobby was the “should have been a scientist” of our family. At 15 he could already explain to me Einstein’s theory of relativity, how we were made of mostly nothing, and that you could not really touch anything because atoms repelled each other. I was fascinated by his stories and more dangerously by his experiments, the most dramatic being how he could take a little yellowy powder (sulfur), mix it with this or that and create little poofs of fire and smoke. Wow! In the kiddy land of our 1950s world, that was downright atomic.

One day, when Bobby was off studying or reading some boring intellectual fare, I borrowed a little capful of his magic sulfur and took it over to Stevie’s, whose family possessed a few large jugs of those cleaning chemicals emblazoned with the word DANGER.

We mixed a few things together, but nothing happened. Then we saw the large barrel of chlorine. We took a pinch of it, mixed it with our last bit of sulfur and waited, but again nothing happened. To give it a little assistance Stevie went in to find some matches. A few minutes later Stevie and I entered the ranks of other great scientists. The match instantly ignited the concoction with a brilliant, gagging, choking, gaseous stench. To me the world of science would never again be as exciting or as educational as it was about to become. In the dusk we ventured off into what should have been our deaths, and if the timing was right the death of everyone in my entire family.

We didn’t know how people got chemicals, but we decided if anyplace would have them it would be the drug store, a short few blocks’ walk. Down every aisle we carefully examined the bottles and powders we thought most promising and worthy of scientific research. There were all sorts of exotic-sounding substances; we considered potassium, rubbing alcohol, hydrogen peroxide and glycerin. Ah, glycerin, we thought. That is at least half of what we need for nitroglycerin. Then I saw it, couldn’t believe it was super-sized, but there it was: a big yellow pint-sized bottle marked sulfur, a sure thing, and absolutely essential for any good research.

Using money we had saved up from neighborhood yard work, we purchased two of the largest bottles they had and headed for the basement at my house. A basement that was just large enough to house a furnace and a table to conduct experiments on. It may have been small but it had all the other essentials: it was dark with gray walls and one naked ceiling bulb for light. Adding to the ambience was a damp earthy odor that fit perfectly with the low growling noises the furnace made. It was precisely the kind of site Dr. Frankenstein would have chosen for his finest work.

It was getting late, almost dinner time, and we decided not to mess around. We went right for the sure thing: the five or six pounds of chlorine Stevie had brought bundled in a large colorful beach towel from his house and the two giant canisters of sulfur, our most prudent purchase.

As the sky turned black, we decided to leapfrog over incremental scientific investigation and simply poured the sulfur, all of the sulfur, into the towel bundling up with the chlorine. It was our intent to go into the back yard and light it. The towel was heavy, and it took both of us to twist the towel ends together and pick up the massive ball. I think it was Stevie that felt it first, “my hands are getting hot.”

It was just one of those fortunate little coincidences in life, that the stairs I was walking up happened to be on the outside of the house and built out of cement. At the first step the towel began to smoke, a few more and I doubted my ability to hold on to the steaming buddle. By the top the towel was in brilliant white flame, we dropped the bundle and fell sprawling into the gravel gasping for clean air. But even as I crawled through Stevie’s vomit and began some of my own, I was able to marvel at the towel which was now a brilliant crystal white light that turned the neighborhood night into day.

I would later be told that the light from the ball of purest white light could be seen at the neighborhood edge and that the chlorine gas created would have terminated everyone in the house had we not managed get it out the door and crawl away. Although my brothers had little to say in any admiring way, Stevie and I had clearly made an impression on our parents who now saw us as scientists to be reckoned with.

New chapters coming once each week — Full book thus far under THE MIRACLE OF ME / autobiography of a nobody

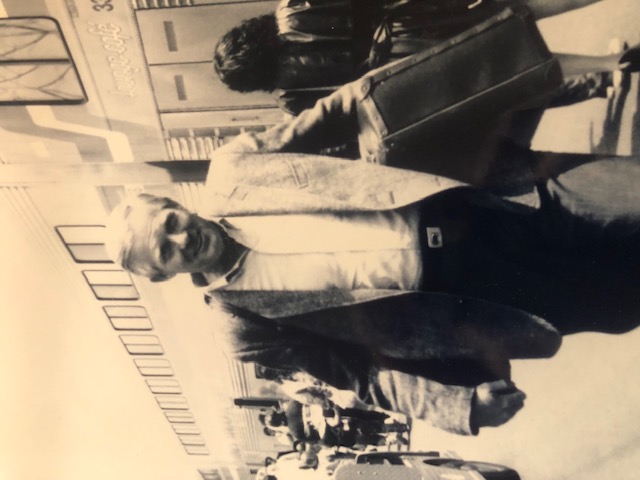

Richard Kimball — Vote Smart Founder

Sign up on my Blog at: richardkimball.org

or

Medium.com at: https://medium.com/@daffieduck2016